YIDDISH SONG AFTER THE HOLOCAUST

The impact of the destruction of European Yiddish culture in the Holocaust upon Yiddish song is clear: the cultural roots of this diverse repertory were razed and collections of songs destroyed alongside their singers. Nevertheless, today Yiddish song continues to thrive and develop in contexts ranging from small cultural clubs to major concert stages, and embraces musical styles ranging from klezmer to hip hop.

Today Yiddish is spoken by around 700,000 people, most of them in strictly Orthodox Jewish communities in the USA, Israel and Europe. Since the 1960s, however, there has also been much interest in Yiddish as ‘heritage’ among young, mainly secular Jews in North America. The people who sing in Yiddish today are both amateurs and professionals, religious and secular, people who grew up with Yiddish and those who know none; people who see in Yiddish an intimate connection with their own roots and people who are simply interested in exploring another folk tradition. Some performances reflect a nostalgic longing for the east European shtetl – and others use Yiddish song as a tool to create forward-looking visions of 21st century diasporic Jewish culture.

CHANGING ATTITUDES TOWARDS YIDDISH SONG

During the first decades of the twentieth century, a number of European Jewish folklorists sought to collect, classify and publish Yiddish songs, particularly folk songs. After the Holocaust, surviving folklorists continued this work with vigour, recognising the value of Yiddish song as a reflection of the lives of a people tragically destroyed. Directly after the war, projects to collect folkloric materials were organised in the Displaced Persons’ camps by central historical agencies that sought to record testimonies concerning the atrocities of the Holocaust. Folklorist Shmerke Kaczerginski, a lithographer and songwriter who had been incarcerated in the Vilna ghetto before living with a partisan group in the woods in White Russia, prepared a book of 236 songs from the ghettos and camps, some with musical notation, which was published by New York’s Congress for Jewish Culture in 1948.

Parallel to the collection of Yiddish songs themselves, a number of documentary recordings have been made throughout the post-war decades, preserving the voices of individual singers. Individuals recorded include Majer Bogdanski, Arkady Gendler, Mariam Niremberg and Lifshe Schaechter-Widman. Alongside these professional recordings, many members of the public have also become involved in recording projects: during the 1970s YIVO (the Yiddish Scientific Institute, based in New York) established a Folk song Project mobilising people to collect songs from Yiddish-speaking immigrants in America.

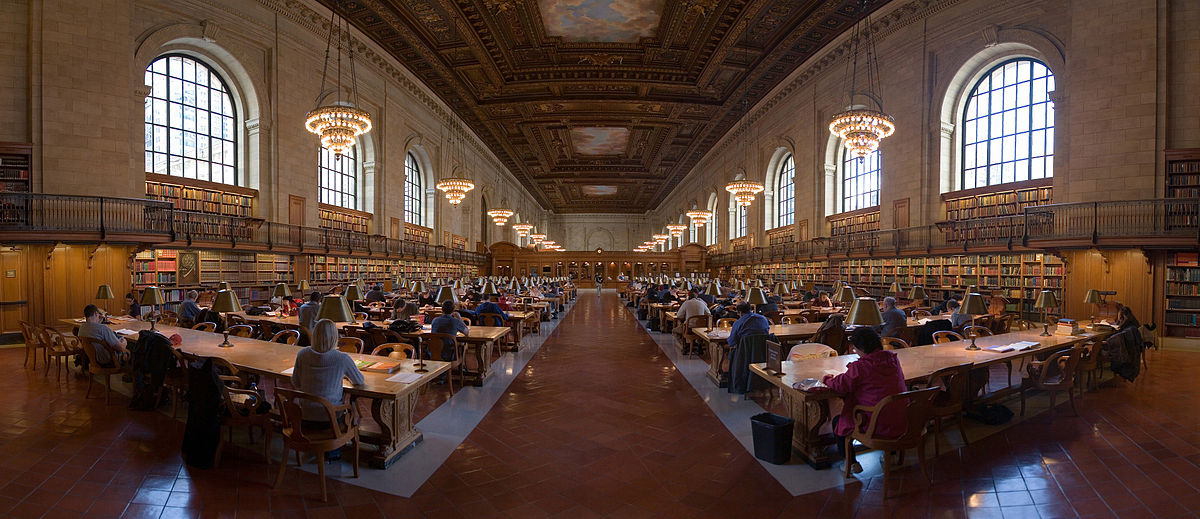

Despite the decline of Yiddish as a spoken language after World War II, during the period 1945 to 2001 over 130 new songbooks containing either exclusively Yiddish songs or a substantial amount of Yiddish material were published (this figure is based on major library collections in New York and London). The majority are collections offering an overview of ‘typical’ Yiddish songs, produced for use at home or in the community, responding to the wishes of a wide audience to engage with this repertory. These books tend to place material of diverse origins (for example theatre songs, art songs, political songs, folk songs and religious songs) side by side, reinforcing the idea that Yiddish song somehow encapsulates the story of Yiddish culture. Frequently the compilers of these songbooks also embellish this story with photographs, anecdotes and explanations of the songs. While this information is often worthwhile, it sometimes encourages an over-nostalgic or sentimental picture of Yiddish culture. It is important to remember that in pre-war Eastern Europe these songs represented very different repertories and performance contexts: the idea of a single category of ‘Yiddish song’ is much more recent.

In recent years, academic interest in Yiddish song has increased: in addition to new research, several pre-war collections, including those of Soviet folklorist Moshe Beregovski, have recently been translated and republished. Other folklorists have sought not only to record and publish Yiddish songs but also to perform them. In addition to publishing a book-length study of Yiddish song, Voices of a People, Canadian-born folklorist Ruth Rubin (b. 1906) collected, performed and published Yiddish songs, making several recordings, including one of Holocaust-era songs.

PERFORMANCE

Many of the contexts in which Yiddish song is performed in the USA today have their roots in pre-war Yiddish culture, which thrived following the arrival of thousands of Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants from Europe during the late 1900s and early twentieth century. While Yiddish cultural activities are held in many cities throughout the world, New York continues to be a cultural centre. There, the Folksbiene Yiddish theatre continues to thrive under musical director Zalmen Mlotek; the weekly Yiddish-language newspaper Der Forverts (Forward) and Yiddish-language radio show Forverts Sho (Forward Hour) both include regular features about Yiddish song. Several Yiddish choirs meet and perform regularly. Songs also form an integral part of today’s Yiddish teaching – songs are included in Yiddish textbooks and singing sessions are frequently held by Yiddish cultural groups which meet regularly in cities throughout the USA, Israel and further afield.

Some post-war performers of Yiddish song in North America have chosen to continue along paths forged by their predecessors. During the mid-twentieth century, Jewish comedian Mickey Katz recorded many Yiddish-English parodies of popular American songs, continuing a Yiddish comedic tradition that began in Eastern Europe and developed in America. Several Jewish stars of show business, including Mandy Patinkin, have performed or recorded Yiddish songs, simultaneously recognising their own Jewish heritage and the contribution of Jewish immigrants to the development of music on Broadway.

Since the 1980s, however, the largest context for the public performance of Yiddish songs in the USA and Europe has been the ‘klezmer revival’. During the 1970s a number of American Jewish musicians began to rediscover European Jewish repertories that had largely fallen into disuse by the middle of the twentieth century. From a few initial ensembles, the revival grew swiftly into a scene which today encompasses literally hundreds of bands, amateur and professional, spanning North America, Europe and further afield. Several yearly klezmer ‘camps’ are held in the USA and Europe, offering classes in Yiddish song.

While in the Old World – pre-war eastern and central Europe – the term ‘klezmer’ (meaning instrument or musician) was applied specifically to itinerant Jewish professional musicians, the revival has turned ‘klezmer’ into a wide umbrella term under which Yiddish music of all origins has been drawn. By contrast with the purely instrumental klezmer ensembles of pre-war Europe, Yiddish song is a core component of today’s klezmer music: the majority of prominent klezmer bands include a singer, or at least have worked with one. At the beginning of the revival, the vocal material most frequently drawn into the klezmer repertory was commercial Yiddish song, particularly that recorded on 78s during the first decades of the twentieth century by immigrant musicians in America. The texts of such songs frequently looked at the relationship between Old World life and ‘modern’ America with wry humour, subject matter which was easily accessible to Jewish-American audiences. As the revival progressed, musicians sought more sophisticated approaches to source material. This was fuelled both by the historical research many musicians were undertaking, and also by a desire to engage with wider issues in Yiddish culture.

Song has become integral to the klezmer scene, providing an important forum for musical and cultural creativity. The best-known singers of the klezmer revival include Michael Alpert (Brave Old World), Judy Bressler (Klezmer Conservatory Band), Adrienne Cooper and Lorin Sklamberg (The Klezmatics).

YIDDISH SONG OUTSIDE THE USA

In Israel, Yiddish culture, including song, did not thrive during the early decades of statehood: the government promoted new Hebrew-language Israeli culture over diaspora cultures. Nevertheless, a revival of Yiddish culture has taken place in Israel since the 1980s, aided by a law passed by the Knesset in 1996 encouraging public awareness of Yiddish culture. While few Israeli singers sing in Yiddish, popular artist Chava Alberstein has recorded several popular albums including Yiddish material since the 1970s.

Since the 1980s interest in Jewish culture has grown in Germany and post-Communist eastern Europe. After the official oppression of Soviet Jews for decades by Communist governments, following perestroika, contact began to be established between American and Soviet Jewish musicians. A number of Yiddish music workshops and festivals are now held yearly in Germany, Poland, Russia and the Ukraine.

Yiddish music was not entirely absent from Central Europe during the post-war decades. A handful of performers sang Yiddish song in East Germany, including Lin Jaldati, a Communist Jew from Amsterdam who had given illegal concerts of Yiddish song during the war before being deported to a series of camps. In 1952 she moved to East Germany, and continued to sing in Yiddish, later joined by other family members. During the 1960s and 1970s some Yiddish songs were also part of student and folk culture, influenced by the repertories of singers such as Joan Baez and the West German group Zupfgeigenhansel; several Yiddish song books were published in Germany.

Since the early 1990s, a sizeable Yiddish music scene spawning many successful local klezmer bands has thrived in Germany and Eastern Europe, mainly among non-Jewish musicians. This has been the subject of much scholarly and public speculation, primarily concerning questions of authenticity and musical ownership. Despite great public enthusiasm there for ‘Things Jewish’, as Ruth-Ellen Gruber has observed, ‘the memory of Jews and Jewish heritage is emotionally charged, whether because of official post-war taboos, government policy, lingering antisemitism, a sincere sense of loss, or guilty conscience’.

The European klezmer revival has formed a significant and welcome source of employment for American Yiddish musicians, whose own Jewish roots and/ or immersion in contemporary Jewish culture have often contributed to their status as visiting experts. Owing to the roots of the language in Middle High German, Yiddish is largely comprehensible to German-speakers, which allows opportunities for performer-audience communication largely absent in English-speaking America; this has been exploited by both German and American Yiddish singers.

RELIGIOUS YIDDISH SONG

The strictly Orthodox Jewish community in America and Israel supports a sizeable popular music industry, which produces music that reflects the religious values of this community. These values are reflected in both song texts and music production: women singers do not appear on recordings aimed at a mixed audience (though a number of womens’ recordings have been made). Yiddish songs appear on many of these recordings. These include songs with explicitly religious content and nostalgic presentations of older songs reflecting pre-war Jewish life. While this music is marketed within the strictly Orthodox community, musical choices frequently reflect outside trends: recently, forays have been made into Yiddish hip hop by artist Lipa Schmeltzer.

CURRENT DIRECTIONS

Yiddish song still draws great interest from the American Jewish community. For many, song is an accessible inroad to a broader experience of Yiddish culture, an anti-assimilation statement and an expression of shared roots and collective identity. Since the klezmer revival, a new generation of young people has grown up surrounded by the sounds of Yiddish music and song. Nevertheless, while few of the older generation of klezmer revivalists grew up knowing Yiddish from home, this number is still smaller in the next generation, and people still alive who remember traditional Yiddish culture at first hand are becoming fewer and fewer.

Enthusiasm notwithstanding, the irreversible loss of the pre-war Yiddish cultural world is a fundamental constraint upon the depth of immersion in Yiddish language and culture available to those who choose to opt into Yiddish today. This lack of cultural and linguistic immersion has shaped the approaches of the new generation of performers towards Yiddish repertory. Performers have tended to gravitate towards theatre and popular song repertories, whose style is closer to familiar American music, rather than traditional folk songs, which require significant attention to an appropriate vocal style. Declining fluency in Yiddish has also had a strong impact on new composition. Learning enough Yiddish to understand songs may be a matter of a few months’ study; nevertheless, much higher fluency is needed to write new songs, and few young Yiddishists are choosing to write new songs.

Nevertheless, artists are continually seeking new approaches to musical materials. Solomon and SoCalled’s Hiphopkhasene (2003) marks the arrival of a new generation of musicians in the Yiddish music scene, using vocal material in both Yiddish and English as a medium of commentary on contemporary Yiddish culture.

By Abigail Wood

SOURCES

Slobin, M. ed., 1982. Old Jewish folk music: The collections and writings of Moshe Beregovski. Philadelphia, PA, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bern, A., 1998. From Klezmer to New Jewish Music: The Musical Evolution of Brave Old World. Available at: www.klezmershack.com/articles/bern.new.html [Accessed January 10, 2002].

Weinreich, M., 1957. Yidishe folkslider mit melodien Y. L. Cahan, ed., New York: YIVO.

Flam, G., 1992. Singing for Survival: Songs of the Lodz Ghetto 1940-45, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Gruber, R.E., 2002. Virtually Jewish: Reinventing Jewish Culture in Europe, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jaldati, L. & Rebling, E. eds., Es brennt, Brüder, es brennt: Jiddische Lieder, Berlin: Rütten and Loening.

Katsherginski, S. & Leivick, H. eds., Lider fun di Getos un Lagern, New York: Alveltlekher Yidisher Kultur-Kongres.

Koskoff, E., 2000. Music in Lubavitcher life, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Lehmann, H., 2000. ‘Klezmer in Germany/Germans and Klezmer: Reparation or Contribution’. Lecture presented at WOMEX, Berlin, 19 October 2000. Downloaded from www.sukke.de/lecture.html, accessed 10 January 2002.

Mlotek, E.G., Mir trogn a gezang: Favorite Yiddish songs, New York: Adama Books.

Mlotek, E. & Gottlieb, M. eds., We Are Here: Songs of the Holocaust, New York: Educational Department of the Workmen’s Circle.

Mlotek, E.G. & Mlotek, J. eds., Pearls of Yiddish Song: Favourite Folk, Art and Theatre Songs, New York: The Education Department of the Workmen’s Circle.

Mlotek, E.G. & Mlotek, J., 1995. Songs of generations: New pearls of Yiddish song., New York: Workmens’ Circle.

Rubin, R., 1979. Voices of a People: The Story of Yiddish Folksong, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America.

Sapoznik, H., 1988. Collecting Yiddish folksongs: a do-it yourself guide for the amateur Yiddish song-zamler, Der pakn-treger/The book peddler.

Schaechter-Gottesman, B., 1990. Zumerteg/ Summer days: Twenty Yiddish songs, New York: Yidisher kultur-kongres and the League for Yiddish.

Shandler, J., 2005. Adventures in Yiddishland: Postvernacular Language and Culture. , Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Silber, L., 1997. The Return of Yiddish Music in Israel. Journal of Jewish Music and Liturgy, 20, 11-22.

Silverman, J., 1983. The Yiddish song book, Lantham, N.Y.: Scarborough House.

Slobin, M. ed., American klezmer: its roots and offshoots, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Vinkovetzky, A., Kovner, A. & Leichter, S. eds., Anthology of Yiddish Folksongs, Jerusalem: Magnes Press.

Wood, A., Yiddish song in contemporary North America. Cambridge University, UK.

Recordings

Alberstein, Chava and the Klezmatics. (1998). Di Krenitse [The Well]. CD recording: Xenophile, XENO 4052.

Bogdanski, Majer. (2000). Yiddish Songs/Yidishe Lider: Melodies Rare and Familiar. CD recording: Jewish Music Heritage Recordings, London, JMHR CD 017.

Brave Old World. (1990). Klezmer music. CD recording: Flying Fish, FF 70560.

Brave Old World. (1994). Beyond the Pale. CD recording: Rounder Records, Rounder CD 3135.

Budowitz. (2000). Wedding without a bride. CD recording: Buda Musique, 92759-2.

Di Goldene Keyt. (1997). Mir zaynen do tsu zingen! [We’re here to sing!]. CD recording: Di Goldene Keyt (no number).

Gendler, Arkady. (2001). My Hometown Soroke: Yiddish songs of the Ukraine. CD recording: Berkeley Richmond Jewish Community Centre (no number).

Klezmatics. (1988). Shvaygn=Toyt: Heimatklänge of the Lower East-Side. CD recording: Piranha PIR20-2.

Klezmatics. (1992). rhythm + jews. CD recording: Flying Fish FF 70591.

Klezmatics. (1994). Jews with horns. CD recording: Piranha PIR35-2.

Klezmatics. (1997). Possessed. CD recording: Piranha PIR1148.

Klezmer Conservatory Band. (1985). A touch of Klez! CD recording: Vanguard, VMD-79455.

Nirenberg, Mariam. (1986). Folksongs in the East European Jewish Tradition from the repertoire of Mariam Nirenberg. Cassette recording: Global Village, C117.

Rubin, Ruth. (1993). Yiddish song of the Holocaust: A Lecture/Recital. Cassette recording: Global Village, C150.

Schaechter-Widman, Lifshe. (1986). Az di furst avek. [As you go away]. Cassette recording: Global Village, C111.

Solomon and SoCalled. (2003). Hiphopkhasene. CD recording: Piranha, CD-PIR1789.

Waletzky, Joshua. (1989). Partisans of Vilna. CD recording: Flying Fish Records, FF 70450.

Leave a Reply